Welcome to the Park

In Point Park, the threads of history intertwine, weaving a rich tapestry of contrasts. Baltimore’s industrial prowess once made it a global powerhouse, its ports bustling with activity. Yet, this progress came at a cost, erasing the native landscape in the relentless pursuit of prosperity and innovation.

The legacy of the Indigenous peoples, the original stewards of the land long before Baltimore’s inception, is a poignant reminder of the city’s roots. Equally significant is the tale of the Serpentine grasslands, a rare ecosystem that harbored the chromium ore crucial to Baltimore’s chromium industry.

In this park, layers of history converge, telling stories of resilience, adaptation, and transformation. It stands as a testament to the intricate relationship between progress and preservation, where the past and present coexist in harmony.

Please do… Be respectful of the space. Stay out of planted areas. Don't let your pets use plant beds as bathrooms. Don't move logs, branches, or rocks and pebbles.

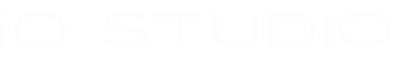

The Plan

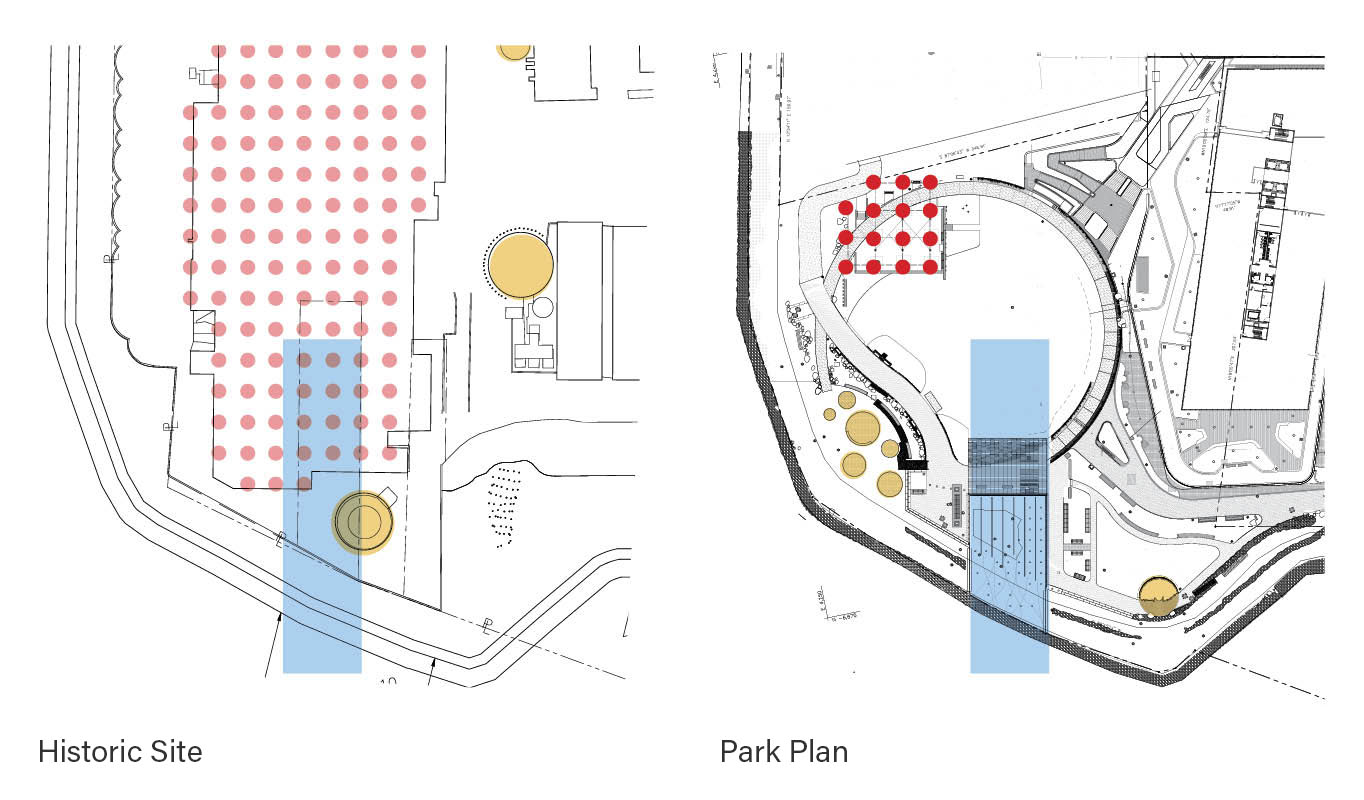

Legend.

Symbolic Steel Gates

Reference site history and Indigenous tradition

The Grove

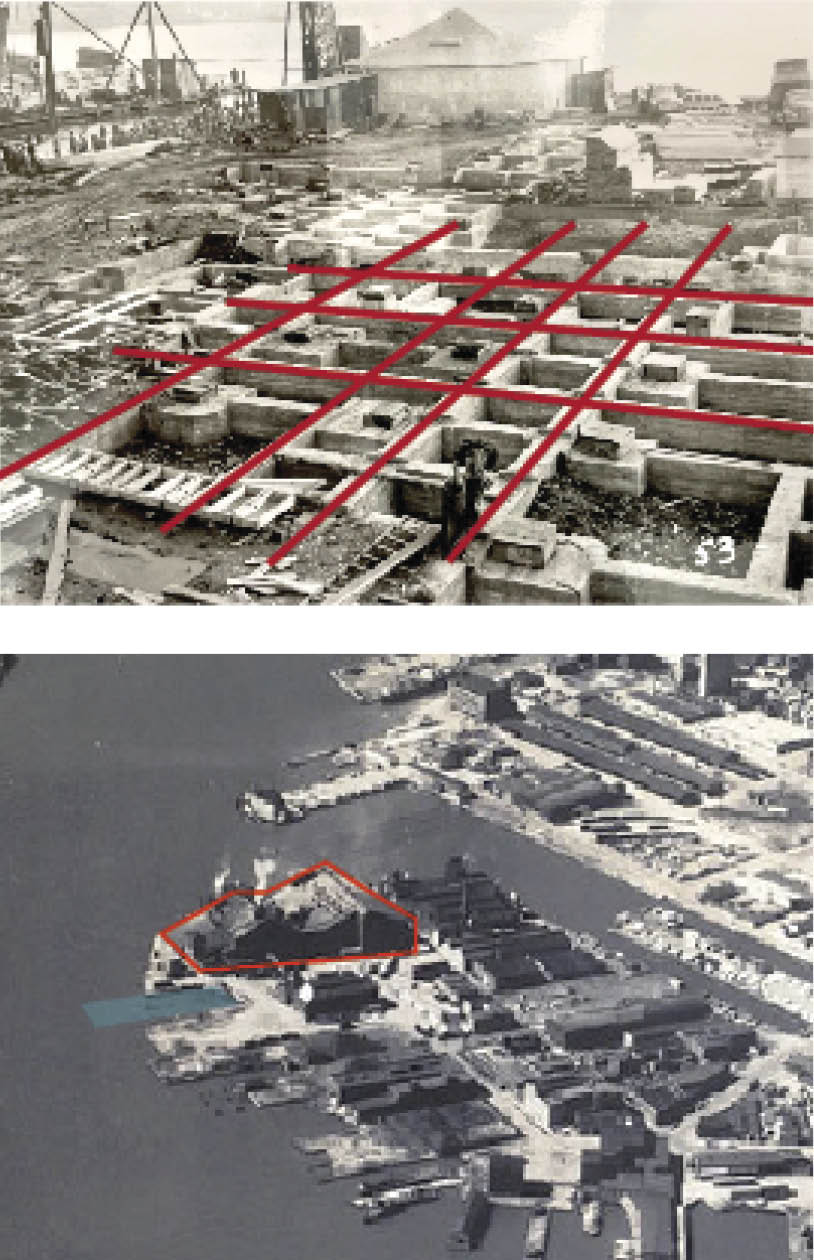

Reference the architectural columns that once supported the main plant

The Covered Slip

Outlines the location of the former boat slip which brought materials to and from the site

Planter on the Point

The crescent planter references the multiple cylindrical holding tanks found on the site.

Planters on South Shore

Similar to the crescent planter, these planted mounds will be the home of a rotational planting display, interpretng both regional landscapes and plants significant to Indigenous culture.

Industry.

Baltimore. Giant of Industry.

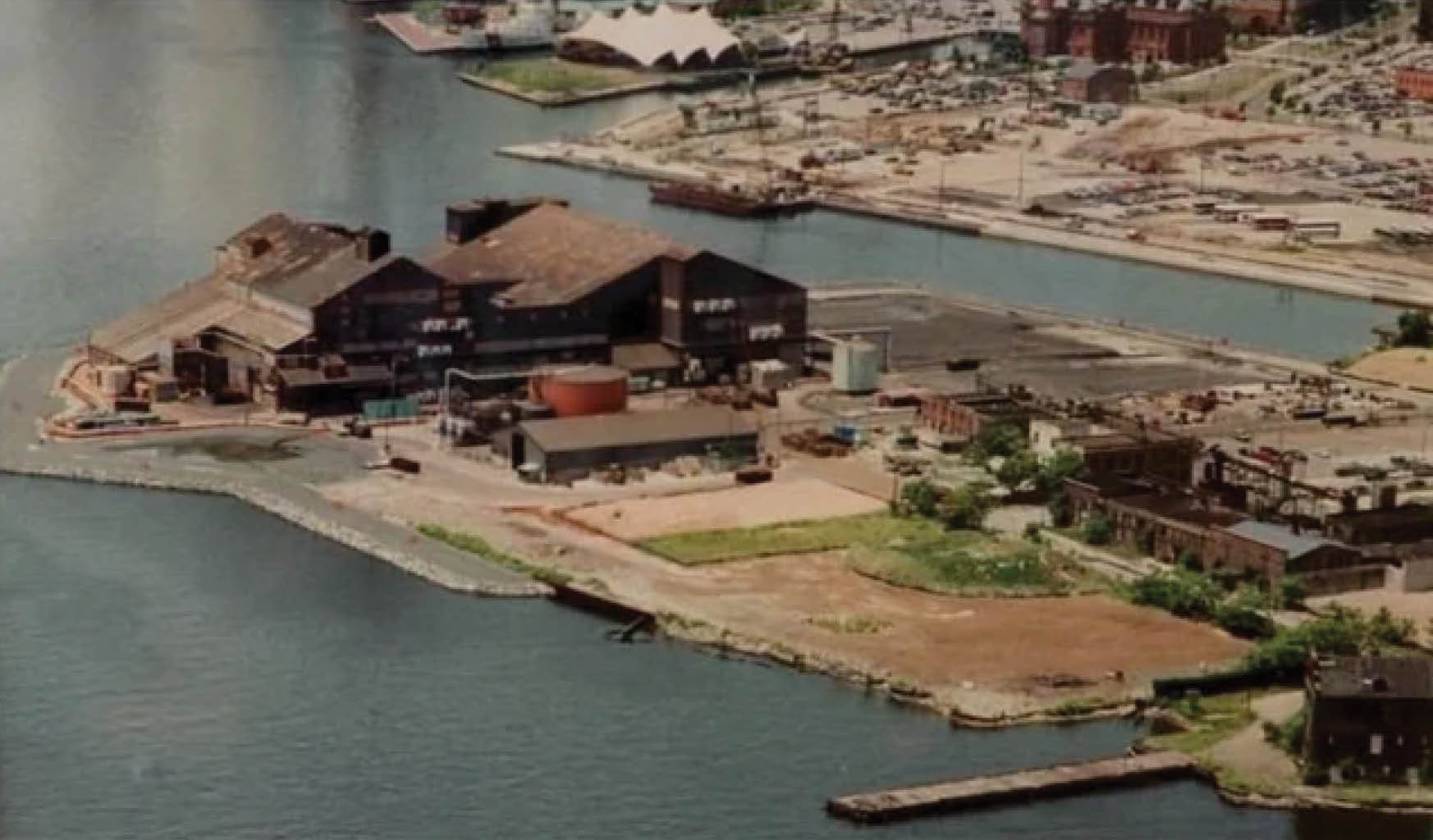

Baltimore Chrome Works, a chromium ore refinery, was headquartered here at Harbor Point. For more than 130 years, the chromium ore refinery was one of the largest manufacturers of chrome ore goods in the world. Isaac Tyson started mining chromite in the area around Baltimore in 1813 and built the Baltimore Chrome Works at Fells Point in 1845. The works became part of Mutual Chemical Company in 1908 and merged into Allied Chemical in 1954.

At its peak, the operation was one of several Baltimore-based industries that helped to establish Baltimore City as one of the centers for industry and innovation in the world.

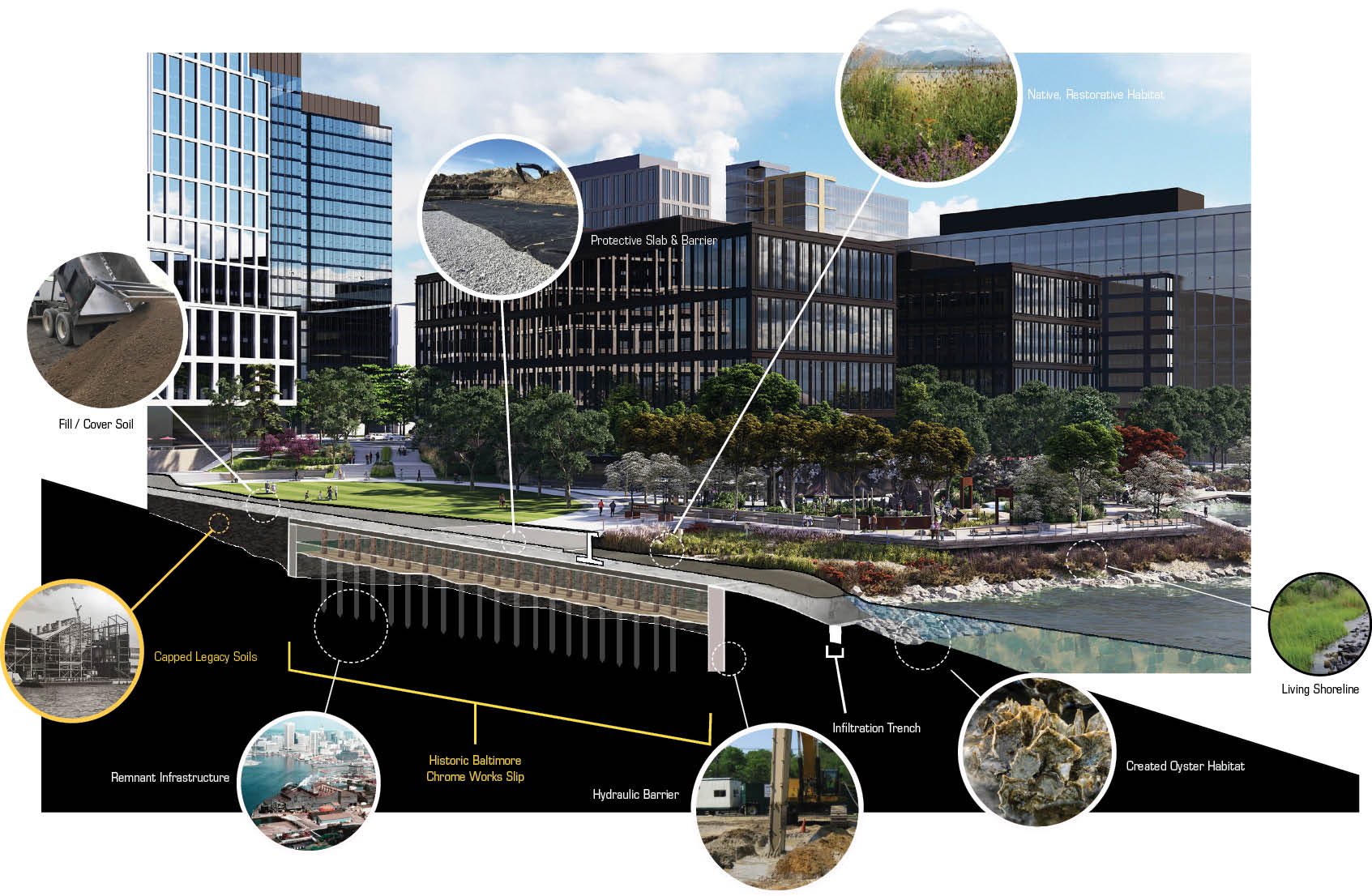

As with most industrial successes, the operation brought with it a legacy of contamination. In 1985, the city, state, and federal government sponsored a lengthy remediation of the site and its surroundings, resulting in the capped Brownfield site we now call Harbor Point.

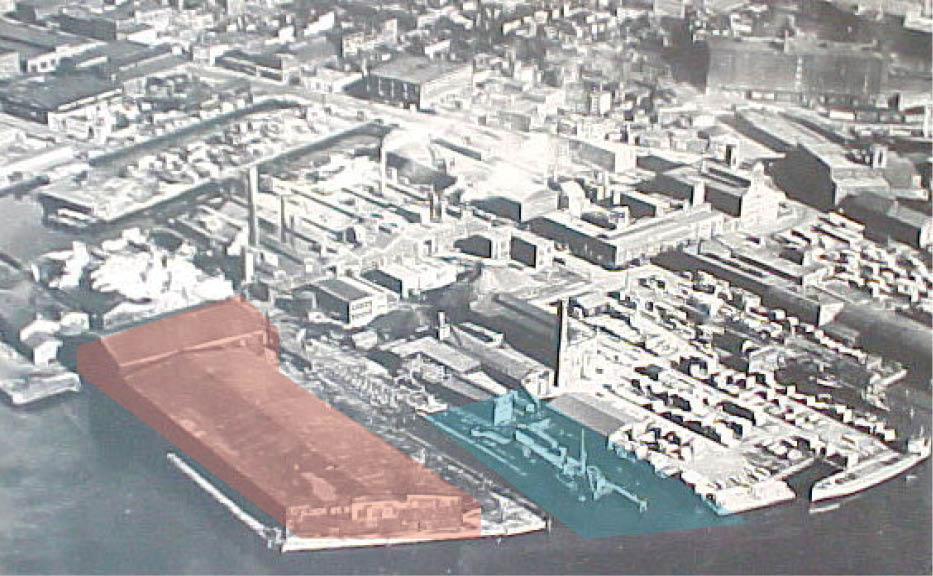

The Historic Slip and the Main Plant - ‘Building 23’

The long buried historic slip is brough back to the surface in the park's design, traced in the lawn with granite pavers and framed along the waterfront with wood deck and plaza space. Where water once brought ships into and out of dock, a sunken plate of native grasses and shoreline plantings is created - the area, designed to withstand inundation in storm events.

The buried foundations of the old mill building are referenced in the park at the grove. Here, slender trunks of oak trees mark the rhythm of the columns that once supported the massive structure.

Seen & Unseen

The story of the park cannot be told without acknowledging the complex history of the site and the legacy of Baltimore’s industrial past. The remediated brownfield site is a story in itself - the methods and strategies deployed in the clean-up and stabilization of the site, concealed from all but the informed eye. However, relaying the story of the site and its return to becoming a key element in the chain of open spaces surrounding the Harbor was an important goal of the interpretive design.

Landscape.

The Serpentine Grasslands

of Baltimore County

Serpentine is valued as a decorative building stone, road material, and, in two Maryland localities, a historic source of chromium ore. During the 19th century, Soldiers Delight and the Bare Hills district of Baltimore City were the largest producers of chrome in the world. In these two locations, chromite is a significant accessory mineral in the serpentine and was mined up until 1860. Several old mines and quarries are still visible in these serpentine barrens.

The plant selections in the park reference the rocky, barren landscape of Soldier’s Delight Park in Baltimore Maryland - the site where chrome ore was mined for Baltimore Chrome Works.

The Lowland Landscape of

the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay lowland landscape is characterized by low, flat, sandy plains dissected by rivers and extensive wetlands. It’s a unique ecosystem with diverse habitats, including forests, wetlands, and the bay itself, supporting a wide range of plant and animal life.

The park landscape is grounded in drift grasses which reference the marshy shores of the Bay and the tributaries that feed it. Future shoreline plantings will expand this unique typology along the park’s waterside edge.

Culture. True Roots.

Land Acknowledgement

‘You are on Native Land. The place now known as Baltimore City was once home to the Pascataway and Susquehenock. A diverse host of folks from Indigenous nations throughout the land have passed through or lived here at different times and still do. In the mid-twentieth century, thousands of Lumbee settled nearby, forming what would become a vibrant, urban intertribal community that exists to this day. All of the United States is occupied native land and Baltimore is no exception.’

A Simple Statement of Fact

The words above, etched into the steel panels along the north wall of the park are a reminder that ALL lands of the United States of America were and are native lands. The traditions and contributions of Indigenous people are still alive today in much of the fabric of contemporary American culture and society. From place names to medicinal teachings, the impact of native culture has been profound and continues to expand our collective awareness of what it means to be ‘American’.

The park lends itself as a canvas upon which the story of Indigenous peoples can be told in small ways and large. Before there was a park, there where was Baltimore Chrome Works. Before the Chrome Works there was a settlement that became Baltimore. Before Baltimore, there were the territories known as America. And before this place we call America existed, there were the Indigenous people who called this place, simply, ‘home’.

A Deeper Connection to the Land

The plant selections within the park speak not only to our regional context, but also shine a light on the indelible connection Indigenous people have with the land. In native culture, plants were a source of food, medicine, dye, construction material, and clothing.

The combination of plants is intended to be as beautiful in their combination as they are useful, and to create a place where one may kindle a new appreciation for our environment – one rooted in the very connection between human beings and our earth.

The expanded narrative moves the interpretive threads of the overall Harbor Point landscape from a simple statement on sustainability and a contemporary reading of the site’s history to one that celebrates the much older knowledge of the earth that Indigenous peoples possessed.

Community.

Community Activists, Artists, and Story Tellers

In 2024, a team of American Indian community leaders, culture bearers, artists, curators, consultants, scholars and allies organized to ensure Indigenous representation would be reflected in this new park. This was primarily accomplished through language and visual artwork etched into corten steel panels you will find on three tall gates and several walls.

The gates identify the cardinal directions and some of their cultural meanings, in both English and Algonkian dialects. Etched into panels on each gate are illustrations of flora and fauna Indigenous to this place, which are also associated with each of the respective directions.

- North / Luwàneyunk (lowan nay yoonk) - Place of cold winds; Asters

- South / Shaoneyunk (sha oh nay yoonk) - Where warmth awakens earth mother; Pine needles, Pinecone patchwork design in specific reference to the Lumbee people

- East / Wapaneyunk (wah pa nay yoonk) - Place of the rising sun; DiamondbackTerrapin, Black Eyed Susan, Switchgrass

- West / Kumhoko Sukelan ( koom ho ko soo kay lon) - Where the waters come to nourish the earth; Hummingbird, Indigo, Bergamot

Native American Artists

Contemporary Native American artists Jessica Clark and Roberto Dyea lent their considerable talents in the crafting of graphics that adorn the gates of the park.

Roberto M. Dyea (Tsi YOO Nah in Native Laguna Pueblo) has come from a long way home from Barstow, California. He started at Barstow Community College for his general education, then in January 2017, he transferred to the University of Redlands, where he earned the San Manuel Excellence in Leadership Scholarship. During his undergrad studies, he used a variety of media, such as painting, oil painting, charcoal, writing, charcoal, graphite, photography, graphic design, and ink. He dived into character design, and manga art, mixed with his tribal heritage to create various pieces that show his tribal culture and personality. Roberto also served as an intern at the New Americans Museum in San Diego, California. He gained the knowledge of immigrants who wished to seek better opportunities and then became Citizens of the U.S.A. along with Oral History when arriving in America. Additionally, he became an advocate for Native American students and Indigenous students as he was Vice President for the Native American Student Union (NASU) and an intern for Native Student Programs. He belongs to the tribe called Pueblo of Laguna.

Jessica Clark is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of NC. She earned a Bachelor of Art in Studio Art from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke and a Master of Fine Arts in Painting from the Savannah College of Art and Design. Jessica has exhibited in numerous shows in the Southeast, and her work is included in numerous private collections along with the Museum of the Southeast American Indian, Savannah College of Art and Design- Lacoste, France, the Federal Reserve Bank in Charlotte, and the NoVo Foundation. Her work concentrates on documenting, preserving, and educating her viewers on Southeastern Native American identity.

Our Team

Amber Chavis (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina), Executive Vice President, Finance and Administration, Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore

Lillian Sparks Robinson (Rosebud Sioux Tribe), Owner and CEO, Wopila Consulting

Ashley Minner Jones (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina), Community-based Visual Artist, Scholar

E. Keith Colston (Tuscarora, enrolled Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina), Administrative Director, Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs, Director of Ethnic Commissions, Governors Office of Community Initiatives

Rico Newman (Choptico Band of Piscataway), Cultural Consultant

Drew Shuptar-Rayvis (Pocomoke Nation), Cultural Consultant

Roberto D’yea (Pueblo of Laguna), Visual Artist

Jessica Clark (Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina), Visual Artist

Briget Parlato, Marketing Manager, Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore

Adam Scott Cook, Visual Artist and Designer

Richard Jones, Founder and CEO, iO Studio, Inc

Max Beatty, Director of Operations, Beatty Development Group

Advisory Committees comprised of representatives of:

- The Baltimore American Indian Center

- The Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs

Further Resources:

Contributing Local Artists

Bridget Parlato is an interdisciplinary artist specializing in cause-related work. Her purpose-driven projects strive to raise awareness and create behavioral change through digital and print campaigns, sculptures, public events, performances, installations, and public outreach.

John Ruppert and Adam Scott Cook both lent their considerable talents to the park. Ruppert’s ‘Lightning Strikes’ sculpture is presented in plantings to the east of The Grove.

Adam Cook, a sculptor in his own right, oversaw the translation of the sketches of flowers and animals by Roberto and Jessica to cor-ten steel. Cook was also responsible for the fabrication and installation of the panels.